02 Wiring up

the Cyber-Elite

If we look into the infrastructure - those wires that sustain the verification marks - we will see that it’s most valuable resource for social media today is 'increase of the engagement' (Venturini, 2019). Online platforms are defined by "radical behaviourism": "they don't care about why their users engage with them, how engagement is generated, or what engagement even means - the only thing that matters is increasing their measures of clicking, viewing, scrolling" (Venturini, 2019). The circuit, powered by the advertisement revenues, which we can imagine as electricity, is not capable of running on air, i.e. ‘quality’ or ‘authenticity’. The truth in question, therefore, is defined by engagement metrics as is any other part of this system. Such truth “is not opposed to falsity” (Amoore, 2019), and more stories from social media whistleblowers are yet to follow the outcry "I have blood on my hands", in which the ex-Facebook employee called out the company declining to take action against fake accounts interfering in politics. It has to do with the fact that 'the expected clickthrough rate (the probability that users will engage with the ad)' defines how much profit will be gained (Venturini, 2019). Even though the accounts were factually fake, they were true in the sense of high numbers of generated users’ engagement and the resulting profit.

The impressive fluidity of something that is supposed to be as fundamental as the concept of ‘truth’ can be traced back to the ‘actuarial age’ - era that predated contemporary discussions on automated surveillance systems (Harcout, 2007; Rouvroy, 2011). Originating in statistical knowledge on populations, actuaries' work was meant to calculate and minimise risks for the insurance industry since the slave trade in the 19th century, the job that is now heavily automated (Ochigame, 2020). Actuarial logic was meant to generalise your future behaviour based on a set of parameters, and such future-oriented reasoning became embedded later in digital information infrastructures (Rouvroy, 2011). It was not the truth in the sense of a control group and the characteristics of its behaviour, against which you can measure the result of the prediction, referred to as "ground truth". Actuarial logic, indeed, was defined by "the lack of ground truth", as the act of prediction actively influences the measured population, making it impossible to create conditions to learn what would happen without such prediction. Translating actuarial logic to today's extremes: we would never know if a person would commit a crime if a drone would not have already killed them based on their metadata.

This notion of truth is then inherited by algorithms that constitute the work of current information infrastructures, including social media networks. The notion of truth that they propose, therefore, "is not opposed to falsity or error of the prediction" - as verified accounts are opposed to accounts without a blue mark not because unverified accounts are fake (Amoore, 2019). The truth is defined by the probability of action to be done based on the data that we analyse. In the case of verification marks such probability is the engagement, which someone awarded with the blue tick is likely to generate. One can highlight such an understanding of truth as engagement based on the changes in the verification policy and their connection to the social media perception of engagement. The tool, invented by Twitter 'to help with cases of mistaken identity or impersonation', has changed significantly since 2009 with the changing structure of tracking/engagement loops, despite the icon, borrowed by other social networks, remaining the same.

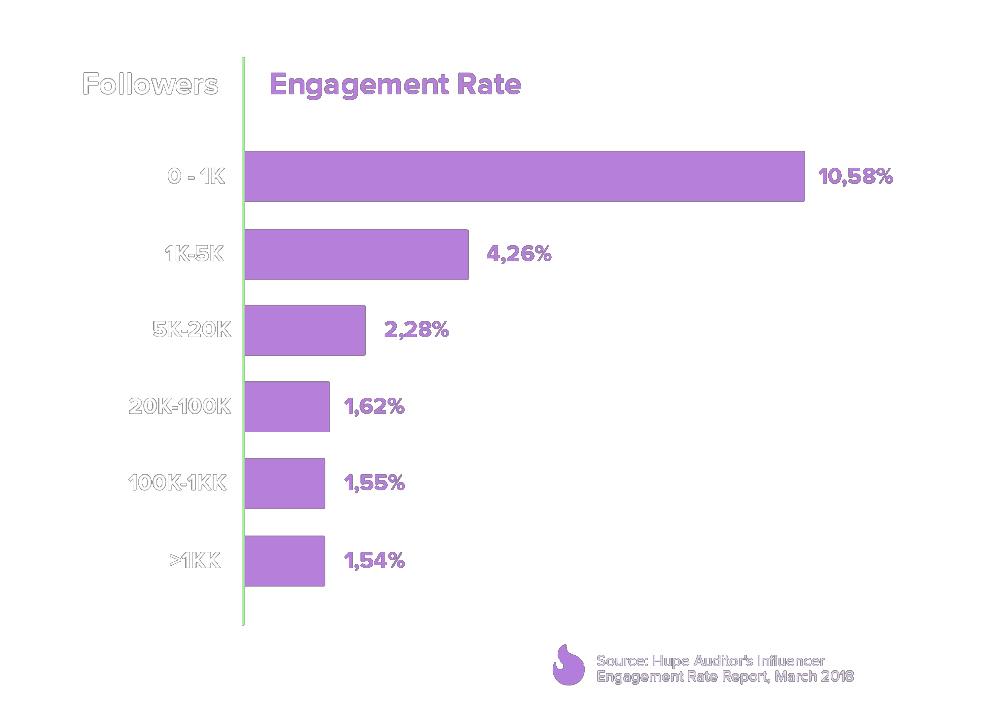

When social networks introduced blue tick verification systems, these platforms were finishing the transition from the 1990's era, characterised by the clear cut distinction between digital class of '"posters", the minority of individuals contributing to the life of digital communities, and "lurkers," the silent majority who just read their discussions' (Venturini, 2019:21). In the 2000s social networks aimed to capitalise on the thinning of this distinction, making it easier for 'lurkers' to produce their own content by reacting through 'social buttons', to maximise and quantify users engagement - one of the main assets in the contemporary digital economy. Nevertheless, at a time when verification ticks were introduced in 2009, the distinction in digital classes between 'posters', rebranded as influencers, and users remained. Even though both could at that point create engagement, this engagement was expected to vary drastically based on how many followers one has, with the numbers being highly polarised. In simple terms, there was no digital middle class. Therefore, the fact that verification marks were granted exclusively to celebrities without any publicly available explanation of the algorithm or opportunity to apply for it did not raise a public debate, as it was following the evident abyss between cyberelite and online masses.

Gradually, the distinction between users and influencers became more and more blurred, giving rise to the phenomenon of micro-influencers around 2016. This new middle class of attention economy was (and still is) believed to be the future of online advertisement, bringing promoting bodies the golden ratio of price and engagement. Micro-influencers have more modest numbers of followers that vary for this category from 1-10K or 10-100K for Instagram and are praised for their 'authenticity' that implies more 'engagement' from the followers (Markerly). This combination allows for advertisement companies to distribute the PR budget more effectively, paying the same price for engaging the network of micro-influencers that they would pay to get advertised by one influencer account. The rise of micro-influencers brought the challenge for the verification policy, as it amplified the value of the blue tick and the need to distribute it for the new class of influencers. This need to assess the rating of new class of users was met in 2016 by the new verification approach from Twitter that allowed micro-influencers to apply for verification: 'our goal with this update is to help more people find great, high-quality accounts to follow, and for creators and influencers – no matter where they are in the world - to easily connect with a broader audience.' Even though it turned out to be harder to trace the history of YouTube verification policy, based on the difference between the 2015 and 2016 tutorials on YouTube verification it is possible to conclude that a similar change happened to the platform policy in 2016.